Scaling a business up can be expensive, and inherently involves risk. Bank lending, among other forms of finance, allows businesses to grow regardless of these constraints by: (i) providing them with the required capital for growth; and (ii) distributing the financial risk of doing business among multiple participants rather than the entrepreneur alone.

This process works buttery-smooth in India when it comes to growing businesses organically (i.e., by building new things from scratch) and would generally look like this in action:

Company. We would like to borrow INR XX crores to set up our 3rd ball-bearing factory.

Bank. Terrific. Let us have our guys assess the risks involved in lending to you. If they’re higher than we like, we’ll offer you the loan on stricter terms than usual.

Company. Sounds like a deal.

But when it comes to growing businesses inorganically (i.e. by acquiring or merging with other companies), the script would always follow a variation of the below:

Company. We would like to borrow INR XX crores to buy that company over there which runs a ball-bearing factory.

Bank. …

Company. ?

Bank. No.

This is because, for all of Indian corporate history, Indian banks have been prohibited by law from lending to fund acquisitions. The world around them, however, has marched on. Acquiring a business often requires an enormous sum of money which most acquirers don’t have lying in their bank accounts. External funding like debt, thus, becomes a critical tool to make deals possible. In the absence of domestic bank-finance, foreign banks and non-bank lenders stepped in to fund the Indian M&A growth story while Indian banks watched resentfully from the sidelines as the number of deals and the average deal size surged over the past decade. They were locked out of a raging party, and they wanted in.

Last month, things changed. Following a formal request by the Indian Banks’ Association reiterating the industry’s long-standing demand to be allowed into the M&A moshpit, the RBI caved. On October 1, 2025, it declared that the Indian banking system was now strong enough to shed its training wheels and, within days, published a draft framework to enable Indian banks to finance acquisitions, titled the ‘Commercial Banks – (Capital Market Exposure) Directions 2025’.

As these things go, the proposed directions are currently in the public consultation stage till November 21, 2025, and remain subject to any suggestions from stakeholders which the RBI may want to build in. However, the move marks a pivotal moment. Not just for banks, but for how M&A deals are done in this country. The aim of this article is to show you exactly why.

How Acquirers Fund Acquisitions (and the Role of Bank Debt)

To understand what Indian M&A has missed out on so far and what it now stands to gain, we must first understand how acquisitions are funded across the globe (i.e., where banks aren’t restricted like in India) and the role bank lending plays in enabling acquisitions.

Broadly, there are 3 sources an acquirer can tap into to fund an acquisition:

- Internal financing. The cash in its bank account, saved up from its own earnings.

- Equity financing. Money raised by issuing its shares (or other instruments which eventually convert into equity) to investors. These could be funds raised via a public offer or via a private investment.

- Debt financing. Money borrowed from lenders, which must be paid off over time. This can be in the form of bank loans, bond issuances, or credit from non-bank institutions.

The preferred mix of funding-sources depends, in large part, on the nature and incentives of the acquirer. Strategic acquirers (i.e., businesses that acquire other businesses to expand/ enhance their own operations) need to look out for things like their credit ratings and leverage on their books while financial acquirers/ private equity acquirers (i.e., entities that acquire companies as investments, to generate returns) (we’re gonna use both terms interchangeably since private equity happens to be the most dominant form of financial investment of our time) rely mainly on debt. Regardless of the nature of the transaction, as you’ll see below, debt availed from banks plays a crucial role.

How Strategic Acquisitions are Funded

Strategic acquirers tend to be large corporations and large corporations are usually in no shortage of readily available cash. Yet, the use of purely internal financing is limited to small acquisitions. When it comes to large transactions i.e. the ones that make the headlines: (i) readily available cash is often insufficient; and (ii) even if it suffices, the acquirer would prefer to maintain enough cash to meet business expenses rather than blowing it on one expensive purchase. You wouldn’t buy a house using just your bank balance, would you? External funding (i.e., equity financing and/ or debt financing), then, becomes necessary.

In most cases, debt trumps equity as the preferred external funding choice by strategic acquirers. For several reasons: (i) issuing new equity is a long and costly process driven by statutory timelines and multiple intermediaries; (ii) new rounds of equity financing dilute existing shareholders’ stakes in a company, which means it comes at the cost of the acquirer’s shareholders’ ownership/ control in the acquirer; and (iii) if the acquirer is listed, issuances can further expose its stock to market-driven fluctuations in price. Debt avoids all these pitfalls while also being cheaper, considering interest payments are tax-deductible in most jurisdictions. The use of equity to finance acquisitions is generally limited to situations where the acquirer is too leveraged to take on more debt and/ or where there has been a recent run-up in the acquirer’s stock price.

So… strategic acquirers love debt the most out of all funding-sources. Let’s now come to their most preferred form of debt. Despite the rise of new lending alternatives, bank finance has remained the most commonly used for acquisitions across the globe. This may be explained by large corporations’ pre-existing relationships with banks allowing them to negotiate favourable terms and their strong balance sheets and revenues allowing them to sustain large loans. On the other hand, bond issuances, much like equity, lose their attractiveness considering the involved time and cost, requiring disclosures/ offer documents, credit ratings, and investor roadshows. Time is often of the essence in acquisitions, particularly those involving multiple bidders. Fancier options like private credit firms, which charge a premium for customisability, are simply not required in the context of a straight-forward business acquisition, when cheaper and simpler bank loans would suffice.

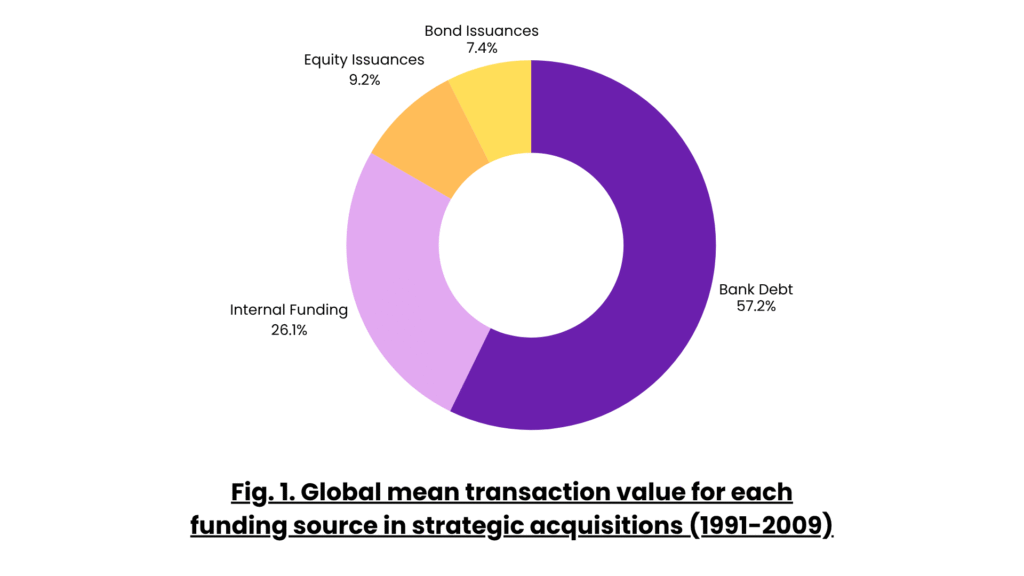

Empirical data agrees with the above hierarchy of preferences. A study examining 610 strategic takeovers across the world from 1991 and 2009 found that an average of ~57% of the transaction value was funded by bank-loans and more than 25% of the takeovers used bank loans as the sole source of financing. Internal funds accounted for a mean value of ~26%, equity issuances for 9.21%, and bond issuances for 7.47% (see fig. 1 above).

How Private Equity Acquisitions are Funded

For private equity acquirers, debt isn’t just the predominant source of acquisition finance. It is the very air they breathe.

This is because the global private equity industry, right since its inception at Kohlberg Kravis Roberts in the 1970s, runs on a neat little piece of financial engineering called “the leveraged buyout” (an LBO). It works like this:

- See a target. A private equity firm identifies a suitable target company and agrees to buy it.

- Pile up the debt. The firm borrows money to fund an overwhelming proportion of the purchase price, often as high as 90%.

- Pay for the rest. The remaining portion of the purchase price i.e., which is not funded by debt, is paid for using the money raised from the private equity fund’s investors.

- Pay the debt off. Once the acquisition is complete, the huge amount of debt raised is paid off over time using the cash flows of the target company.

Think of it this way: (i) you take a loan and buy someone’s house; (ii) they are now responsible for paying back that loan – and if they don’t, the house they’re living in (which you now own) will be forfeited to the lender as security. LBOs allow private equity firms to conduct multi-billion dollar acquisitions by putting up only some of their own money. The firm’s liability is contained only to this amount, while the liability to repay debt rests with the target and is secured against the target’s assets.

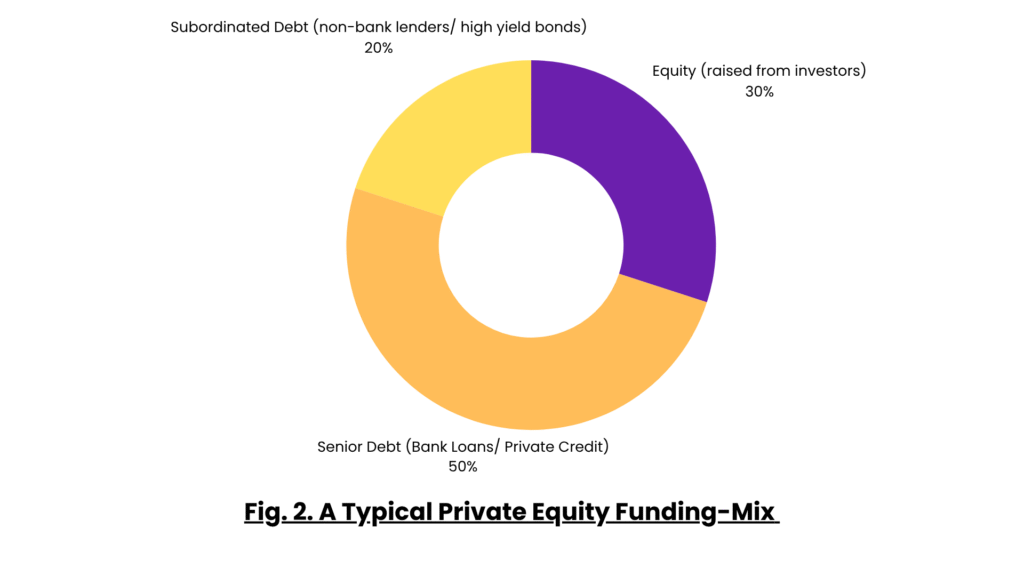

The ridiculous portion of debt in the funding-mix for an LBO consists of multiple layers, each representing a different debt category with a different risk profile. This is because: (i) the overall debt required for a multi-billion dollar deal is understandably too much risk for a single lender or class of lenders; and (ii) having a variety of debt allows the acquirer flexibility in repayment and cost. A typical LBO debt-stack looks like this:

- Senior debt (40-50% of the overall purchase price). Loans raised from a group of banks acting together (called “a syndicate”), secured by the assets of the target. This is the cheapest layer of debt and carries the least risk, since it’s secured. In larger deals, there may be several sub-layers of secured debt, varying based on term and the types of assets used as security.

- Subordinated debt (20-30% of the overall purchase price). Unsecured (and thus, riskier and more expensive) debt. The name “subordinated” comes from the fact that the borrower’s obligations to the senior creditors need to be fulfilled before the subordinated lenders can be repaid. Such debt could be raised in the form of loans from non-bank lenders who have the requisite risk appetite or by issuing high-yield bonds (which are subscribed to by non-bank lenders), or both.

Being the go-to source of senior debt, bank lending takes the spotlight once again. Over the past decade, private credit funds – non-bank entities which lend out money raised from their investors and are not subject to the strict lending requirements imposed on banks – have emerged as a dominant source for financing LBOs alongside banks. Interestingly though, some of the biggest investors in these private credit funds are the same banks they are competing with. The relevance of commercial banks as a source for LBO debt remains far from fading away.

Funding Restrictions in India (and How People Got Around Them)

While bank debt fuelled M&A activity across the world, as we saw above, Indian bank debt was always off limits for an acquirer in India. The restriction on such debt wasn’t the result of a single prohibitory provision, but a product of a variety of legal obstacles:

- Lending restrictions. Paragraph 2.3.1.9 of the RBI’s Master Circular on Loans and Advances dated July 1, 2015 (the Master Circular), prohibits banks from providing loans / advances “to take up shares of other companies,” including funding a promoters’ contribution towards the equity of a company. Indian banks are thus barred from funding any sort of acquisition activity, for both strategic and private equity acquirers alike.

- Restriction on using target’s assets/ shares as collateral. Paragraph 2.3.1.8 of the Master Circular restricts Indian banks from granting advances against any shares purchased using the credit facility provided. Meanwhile, the Companies Act, 2013, prohibits public companies from providing any financial assistance for the purpose of acquiring their shares, which includes providing any assets as security. Together, these provisions lead to the outcome where: (i) you cannot use a target’s shares as collateral, unless you’re raising debt from a non-bank lender; and (ii) you cannot use a target’s assets as collateral, unless the target is a private company. While these restrictions may hardly be of concern to strategic acquirers (since they have their own assets to provide as security), the ability to use a target’s assets as collateral is a central feature of the private equity/ LBO model.

With the above restrictions in place, debt-funding of acquisitions in India has remained suppressed compared to the rest of the world because, in effect: (i) acquirers (strategic or private equity) cannot fund acquisitions using Indian banks and need to rely on (often, more expensive) debt from non-bank lenders or foreign banks; and (ii) in availing non-bank credit as well, using a target’s assets / shares as collateral is severely restricted. Evidencing this suppression, a study involving a sample of 1,041 strategic acquisitions by Indian listed companies from 2000-2018 finds internal funding to have been the most common source of acquisition-funding, equity the second, and debt the least.

The policy intent behind maintaining these restrictions revolved around the idea that acquisitions are too risky an activity for banks to bet their depositor’s money on. Fuelling this concern further was the fact that Indian banks at the time had not yet developed effective systems to manage risk. All of the 2010s were marked by a ‘non-performing assets’ (or simply, ‘bad loans’) crisis wrecking the balance sheets of banks, which the RBI was working on overtime to bring to an end. This was coupled with the regulatory view that acquisitions did not create any new assets (as opposed to, say lending for the construction of a road or factory), and, therefore, were not ‘productive’ investments. The way RBI saw it, acquisitions were ‘too much risk to create nothing.’

But acquirers in India needed their debt. And so, alternative methods of borrowing were born.

Borrowing from Abroad

The most intuitive idea was to turn to loans from foreign banks. But the everlasting arms of Indian law reached out to strangle this route as well. Indian entities cannot avail foreign bank loans to buy a company’s shares since the RBI’s guidelines on ‘external commercial borrowing’ (ECB) explicitly prohibit the use of ECB in India to buy equity. Meanwhile, while foreign acquirers can avail loans from foreign banks, they are restricted from using the Indian target company’s shares or assets as collateral under Indian foreign exchange law1.

With foreign bank loans out the window, the Indian M&A industry devised a workaround for acquirers to fund acquisitions by raising money from abroad. This route involves an Indian entity (this could be an Indian acquirer or a wholly-owned Indian subsidiary set up by a foreign acquirer) issuing listed2 non-convertible debentures (NCDs) to foreign banks/ lenders registered as “foreign portfolio investors” i.e., the category of foreign investors who are allowed to subscribe to NCDs in India. By lending via NCDs, the FPIs are permitted to secure their loans against the target’s shares, assets and/ or guarantees.

This remains the most common way acquirers raise foreign debt to do deals in India. A recent example of this route can be seen in this year’s INR 6,400 crore acquisition of Sahyadri Hospitals Private Limited by Manipal Hospitals Private Limited, which was funded by INR 5310 crore of debt raised via listed NCDs issued by Manipal Hospitals to 5 foreign banks (DBS Bank, Deutsche Bank, SMBC, MUFC Bank and BNP Paribas) purchasing the NCDs as FPIs.

Borrowing from India

Alternatives were developed to borrow from within India as well:

- Issuing listed NCDs to domestic investors. Instead of issuing listed NCDs to foreign lenders (as we saw above), acquirers (or investment vehicles set up by them) can issue these NCDs to Indian lenders. NCDs are the most common domestic acquisition-funding route, mirroring their popularity in raising foreign debt. In a recent example, Mankind Pharma funded INR 10,000 crore of its INR 13,768 crore acquisition of 100% of Bharat Serums and Vaccines by issuing listed NCDs and short-term commercial papers to Indian mutual funds and insurance companies. The NCDs were secured by a pledge on 39.68% of Mankind’s shareholding in the target.

- Borrowing from non-banking financial companies (NBFCs). Domestic lenders registered with the RBI as NBFCs do not face a bar on financing acquisitions because they are governed by a separate, slightly-looser legal framework than banks. RBI’s requirements for NBFCs on setting aside capital as back-up money in case there is a default on a high-risk loan (called ‘provisioning’) leads to NBFCs charging higher interest on such loans.

- Borrowing from alternative investment funds (AIFs). ‘AIFs’ is the name given by Indian law to investment vehicles which pool investors’ money and invest them in non-traditional, higher-risk assets, and are among the most lightly regulated forms of investment. A lot of them offer bespoke private credit services tailored to fit a borrower’s needs, and for such flexibility, they tend to be among the most expensive sources of debt.

- Issuance of compulsorily convertible preference shares (CCPSs). CCPSs aren’t debt instruments. But they aren’t equity either. They exist in the dark and mysterious void in between, till they convert into equity after a pre-decided time period (thus the name, ‘compulsorily convertible’). Raising money by issuing CCPSs enables an acquirer to avoid taking on debt while also limiting the dilution of shareholding that would result from issuing equity. And often, you’d find lenders who are into just this kind of freaky stuff. This year, Jubilant Beverages Limited’s $1.5 billion acquisition of Coca-cola’s Indian bottling arm, Hindustan Coca-Cola Holdings Private Limited, saw Jubilant raising $600 million by issuing CCPSs to Goldman Sachs Asset Management Hybrid Fund, a fund focused on investing in hybrid instruments… like CCPSs.

The RBI’s Draft Directions

The RBI’s draft ‘Commercial Banks – (Capital Market Exposure Directions), 2025,’ expected to take effect from April 1, 2026, adopts a cautious approach in allowing bank-led acquisition finance, aimed at addressing the risks that have kept the ban in place for so long. Here’s what they say:

- Eligible acquisitions. Acquisitions of all or a controlling portion of a target’s shareholding or assets, which give the acquire control over the target. Basically: control deals and buyouts.

- Eligible acquirers. To avail acquisition finance from Indian banks, an acquirer must:

- be an Indian listed company;

- be a strategic acquirer; and

- have a “satisfactory net-worth” and profits for the last 3 years.

- Eligible targets. The entity being acquired must:

- be an Indian or foreign company; and

- not be a related party of the acquirer.

- Eligible security. The loan must be fully secured by the target company’s shares. In addition, assets of the acquirer or the target may be secured.

- Lending caps.

- Banks can lend up to 70% of the acquisition value (which must be determined 2 independent valuers), while the other 30% must come from the acquirer’s own fund (i.e., not other debt); and

- the overall exposure of a bank cannot exceed 10% of its tier 13 capital.

Contrary to some expectations, the draft regulations make it abundantly clear that they aren’t the beginning of a hysterical new age of LBOs and hostile takeovers like in the United States in the 1980s. Private equity acquirers remain barred from accessing Indian bank-debt. And so do unlisted and listed-but-unprofitable companies (like Ola Electric and other listed new-age startups). The intention is to limit bank lending to large Indian corporates, a small subset of the ‘safest’ borrowers. The playground is made even smaller with the regulations limiting lending only to acquisition of controlling stakes. But large corporations tend to make the biggest acquisitions. While the pool of potential borrowers may be small, the regulations capture a sizeable chunk of the potential transaction volume.

Despite the 70% cap, it is unlikely that large acquisitions will involve as high a share of Indian bank debt. The lending cap on banks of 10% of their capital and other pre-existing internal risk controls (such as provisioning requirements under the Basel III system) see to it that banks do not have the risk appetite to write such large cheques. As a further result of their diminished stomach for risk, acquisition finance from banks is likely to come with covenants and restrictions on the borrower (like all bank lending, across the world)… which aren’t exactly pleasant to be subjected to. Consequently, while we may see tiny deals being 70% bank funded, Indian bank debt is likely to be only a part of the debt-mix in larger transactions alongside NCDs and non-bank borrowing.

But, as a competitive advantage, Indian bank debt is likely to be cheaper. While interest rates in India have historically been higher than the rest of the world, they have steadily declined over the past 2 decades to levels comparable with developed economies. This means the cost-advantage of borrowing from abroad has gradually eroded away. This creates an environment for Indian banks to compete on cost with foreign acquisition financiers. Bank loans are also a cheaper option compared to the procedural/ logistical costs of issuing NCDs or the premia charged by non-bank lenders.

On the flip side, it’ll probably take a while for Indian banks to build the talent and expertise to finance M&A. Funding acquisitions is fundamentally different from other lending. It requires an assessment of the future performance of a combined business that doesn’t exist yet, an understanding of complex acquisition structures, and commercial judgment. Banks abroad have dedicated acquisition finance desks to perform this role. Indian banks seem to be addressing this hurdle already. The State Bank of India is reportedly considering creating a ‘centre of excellence to groom and nurture talent and an ecosystem for merger and acquisition.’

The backdrop of growing internationalisation of Indian banking against which the RBI has rolled out its directions is hard to ignore. Just in the past few months: (i) UAE’s Emirates NBD acquired a 60% stake (worth $3 billion) in RBL Bank; (ii) Japan’s Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation acquired a 20% stake (worth $1.6 billion) in YES Bank; (ii) global private equity behemoth Blackstone acquired a 10% stake (worth $705 million) in Federal Bank; and (iv) reports emerged that the Indian government plants to hike the foreign investment limit in government banks to 49%. Meanwhile, rhetoric from the RBI lately has been in sharp contrast to the old view seeing acquisitions as ‘unproductive’ activity. Fun times ahead.

Footnotes

- Cross-border capital account transactions (i.e., transactions involving assets with a long term view) are not permitted under Indian foreign exchange law unless specifically allowed. ↩︎

- Unlisted debt securities are subject to end-use restrictions on investments in capital markets under the RBI’s Master Directions on Non-resident Investment in Debt Instruments, 2025. ↩︎

- A bank’s equity share capital and its retained earnings. ↩︎