In the latter half of the 2010s, a popular way to set up a new tech startup in India went like this:

- Set up a holding company (i.e. one that does nothing but hold shares of another company) in a foreign country (we’ll call this, a “Foreign HoldCo”).

- Set up an Indian company as a wholly-owned subsidiary of this Foreign HoldCo to handle actual business operations (we’ll call this, “Indian WOS”).

The idea was to place the ownership of your business in a foreign jurisdiction to avoid the hassles and red-tape associated with doing business in India, while doing business in India. Foreign markets were also seen as more attractive for fundraising, with doubts surrounding Indian investors’ willingness and ability to understand such startups’ technology-driven, move-fast-break-things approach toward business. In line with the financial world’s long-standing tradition of terrible nomenclature, this structure came to be known as a “flip” because, well, it flips the ownership of a company to another jurisdiction.

Lately, several Indian startups have been owning up to the fact that flipping wasn’t the masterstroke they thought it was, leading them to now consider “reverse-flipping” i.e., transferring their ownership back to India from foreign jurisdictions. Zepto, PhonePe, Dream11, RazorPay, and Groww, have made the trip back in the past year or two. Meanwhile, Flipkart, PineLabs, Meesho, Udaan, and LivSpace are each at various stages of the reverse-flipping process.

This wave is a culmination of several realities that have dawned on foreign-incorporated startups over the years:

- Foreign markets don’t always love you back. Your dreams of raising funds in the US for your e-commerce platform don’t look as promising when you’re hunting for the same capital as companies operating at the frontier of human technology. And if you happened to be competing with these companies during the ‘funding winter’ that swept the globe from mid-2022 to mid-2024, the agonising lesson in humility likely left a lasting impression.

- Indian markets have grown to love you. Meanwhile, the Indian investment landscape (both, public and private) has undergone a real glow-up. Indian stock markets, driven by frenzied retail participation, have been heaping high valuations upon companies looking to go public, including new-age startups. Indian investors know these startups and are better placed to understand the value and potential of their products/ business models because they operate in India. As no surprise, many startups (Zepto, Groww, and PineLabs, for instance) have returned with the explicit goal to list on Indian exchanges. Private capital in India has also been made increasingly accessible by a fairly well developed venture capital/ private equity ecosystem which was all but absent a decade ago, which includes foreign giants now willing (often, eager) to invest in Indian-incorporated startups.

- Compliance is easier when you stay home. Doing business in any jurisdiction requires compliance with the local law governing sector-specific business activities, foreign investment, and taxation. And when you’re located in 2 countries, it’s twice the compliance burden. At the same time, Indian regulators have a track record of preferring local firms over foreign-owned ones for allotting key operational licenses, particularly in tightly-regulated sectors like fintech.

- The loosening death-grip of Indian law. The Indian government really wants these startups to return. More companies incorporated in India = greater tax revenue, more investment opportunities for Indian investors, and localisation of the value created. The government’s intent has materialised in recent reforms, which include: (i) simplification of the merger process between foreign and Indian companies (more on this later); (ii) permitting a wider variety of ways to make cross-border investments (more on this later as well); and (iii) abolishing the abhorrent ‘angel tax’ on startup investments.

On the heels of this blossoming trend, this article unpacks the legal mechanics of a reverse-flip to India by examining the 2 most common methods under the law to pull it off: (i) inbound mergers; and (ii) share swaps. When you see the next foreign-headquartered startup confronting the awkward truth, we hope you’re sufficiently equipped by the end of this article to know exactly how many all-nighters its lawyers are in for.

Inbound Mergers

The most common reverse-flipping method used by foreign-held startups in India is to merge the Foreign HoldCo into its Indian WOS. The Foreign HoldCo ceases to exist and the Indian WOS inherits any assets, liabilities, or employees it may have. The shares of the Foreign HoldCo are extinguished and its shareholders are allotted a proportional number of shares in the Indian WOS. Inbound mergers have been the most popular reverse-flipping route in India, having been embraced by Zepto, Groww, and PepperFry, among others. This is largely because it saves money for shareholders – such transfers of ownership (i.e., which don’t involve selling or buying of shares) do not attract capital gains taxes.

Undertaking these mergers used to be a fairly cumbersome process (taking anywhere between 6-18 months) up until September 17, 2024, when the government simplified things through a legal amendment.

Below is a quick rundown of: (i) how the inbound merger route worked prior to the 2024 amendment; and (ii) the new simplified procedure now in force.

The Old (and Annoying) Way

Before September 17, 2024, inbound mergers of foreign holding companies into their Indian subsidiaries were treated like every other merger1, requiring the supervision of the National Company Law Tribunal (“NCLT”). The NCLT’s role was much like that of a godman in a marriage i.e., serving little purpose, as it ushered the parties through one ritual after another, but seen as necessary nonetheless as a product of tradition.

In effect, the old inbound merger process looked like this:

- Preparation of merger scheme. The merging companies draft a merger scheme describing how the proposed merger will work, including details on the transfer of assets, liabilities, and employees, and the ratio in which shareholders of the foreign entity will receive shares in the Indian subsidiary.

- RBI’s (deemed) approval2. Cross border mergers require the transferor company to obtain prior approval from the RBI, because inflows and outflows of foreign exchange can impact the financial stability of the country and financial stability is the one job RBI has. But things were made easier in 2018 with the introduction of the Foreign Exchange Management (Cross Border Merger) Regulations, 2018 (“FEMA Merger Regulations“), because of which such RBI approval is now deemed to be provided if a merger is conducted in compliance with its conditions. These conditions require nothing but for the merging companies to follow existing foreign exchange law while transferring, valuing, and reporting the movement of money/ assets in the merger. This means that the transferor now only needs to submit a certificate from a director at the time of initiating a merger promising compliance with the FEMA Merger Regulations instead of dealing with the RBI in any manner. Actual approval of the RBI would only be required if the merging entities wish to bend the provisions of the FEMA Merger Regulations for some inexplicable reason.

- Application to the NCLT. The Indian WOS makes an application to the NCLT3 to initiate the merger, and provides them with the merger scheme and other information about the Company required by the NCLT to assess the scheme4.

- NCLT’s initial order. There are 3 things the NCLT can do on examining the scheme:

- Dismiss the application.

- Order the applicant company to hold a meeting of its shareholders and creditors to hear their thoughts on the scheme and get their approval.

- Do away with the requirement to hold a shareholder/ creditor meeting, provided that the applicant company: (i) produces an affidavit recording the consent of an overwhelming majority of its shareholders/ creditors to the merger; and (ii) fulfils certain pre-conditions to the merger, as may be seen necessary by the NCLT. Since an Indian WOS is owned by just 1 shareholder in flipped structures i.e., the Foreign HoldCo (whose consent to the merger is guaranteed), this limb is the most likely path that the merger process takes in a reverse-flip. The pre-conditions imposed usually relate to notifying any remaining stakeholders (such as unsecured creditors) and regulatory authorities (such as the Registrar of Companies (“RoC“), income tax authorities, the RBI, the CCI, and sector-specific regulators) about the merger.

- NCLT’s final order. The Indian WOS returns to the NCLT after notifying the unsecured creditors and regulators, and addressing any objections they may have raised. The merger is then approved and an ‘effective date’ is fixed by the NCLT from when the merger will be viewed as officially complete i.e., the Foreign HoldCo will stop existing and the Indian WOS will survive as the merged entity.

The New (and Quicker) Way

As you may have realised reading the wall of text above (or skipping it), the baptism of paperwork and NCLT visits required to return to the motherland was the source of a lot of pain for startups. The government listened, and changes were made.

On September 17, 2024, mergers of all foreign holding companies into their wholly-owned Indian subsidiaries were made eligible5 for “fast-track mergers”. Fast track mergers are a quick and simplified6 route offered to certain types of mergers which the government feels are unproblematic enough to be conducted wholly without NCLT supervision. Consider it as a highway some companies can take to skip the traffic jam. The fast-track route was previously available only for mergers between: (i) ‘small’ companies; (ii) domestic holding companies and their wholly-owned subsidiaries; (iii) startups; and (iv) a startup and a small company.

Following the above amendment, an inbound merger looks like this:

- Preparation of merger scheme. Same as before.

- RBI’s (deemed) approval. Same as before, the only difference being that RBI approval must now be obtained by both merging entities, instead of the transferor alone. This just means that the certificate promising compliance with the FEMA Merger Regulations must now be filed by the Foreign HoldCo and the Indian WOS, both.

- Notice to the RoC. The merging entities notify the RoC about the merger along with a declaration of solvency. If the RoC has any objection or suggestions, it must raise it within 30 days.

- Shareholder/ creditor approval. The Foreign HoldCo and the Indian WOS each holds a meeting of its shareholders and creditors. Any objections/ suggestions provided by the Registrar in (3) above are discussed. Here, the merger scheme must be approved by: (i) shareholders that form at least 90% of the company’s shareholding; and (ii) 9/10th of its creditors.

- Approval by the RoC and the central government. Within the next 7 days, the scheme as approved above is sent once again to the RoC and now also the central government. The scheme is registered by the central government and the merger is complete If the RoC has no objections. If it does, the objections must be communicated to the central government within 30 days. If, based on these objections / suggestions (or even otherwise), the central government finds the scheme to be against public interest or the companies’ creditors, it may ask the NCLT to examine the scheme and the merger will undergo the old NCLT-supervised process if the NCLT accepts.

Share Swap

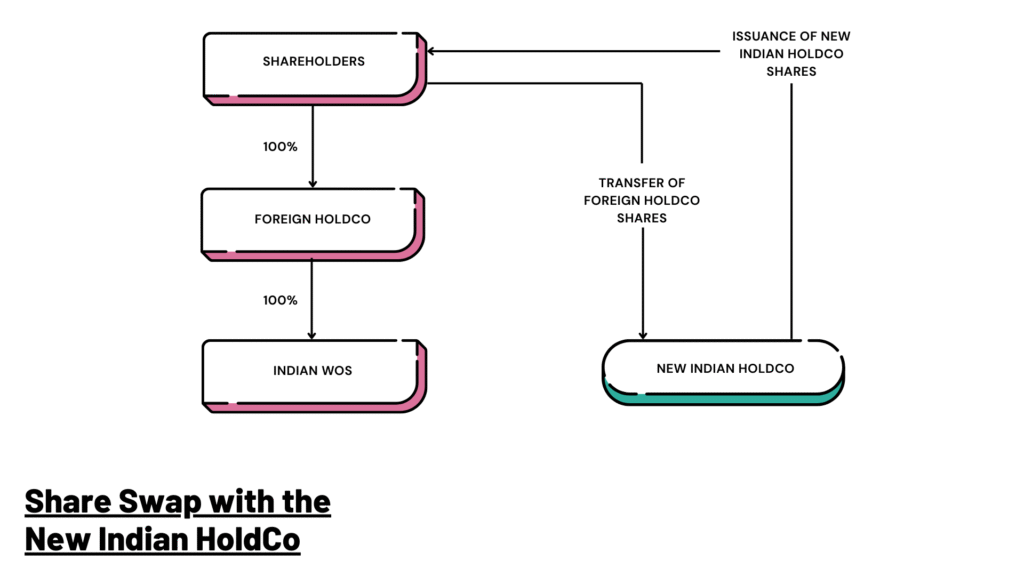

A less common way of reverse-flipping to India is to arrange a transaction where:

- A new company is incorporated in India (we’ll call this, the “New Indian HoldCo”).

- The shareholders of the Foreign HoldCo transfer their Foreign HoldCo shares to this New Indian HoldCo.

- In return, the New Indian HoldCo pays the shareholders by issuing them its own shares in exchange.

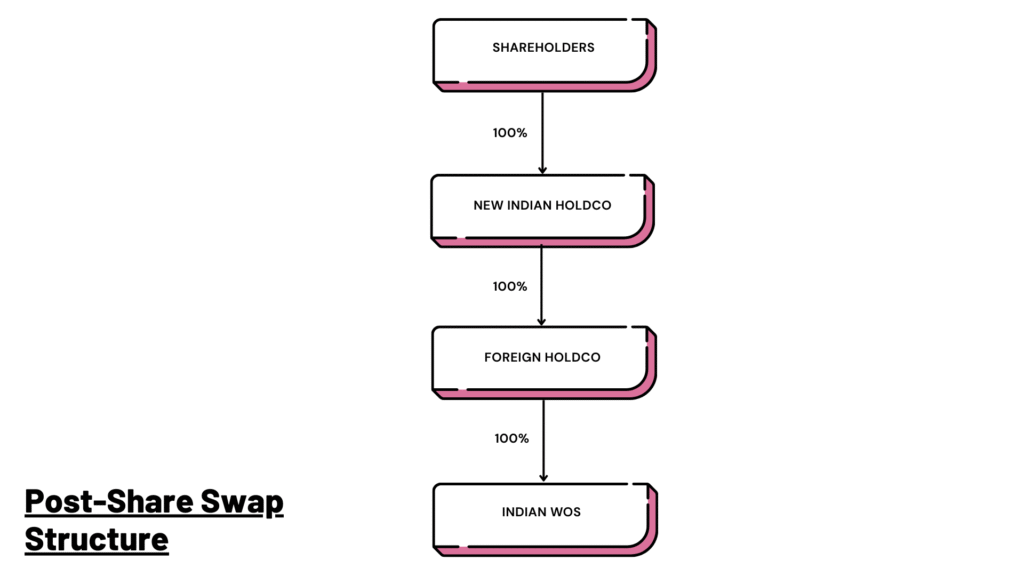

As a result: (i) the shareholders now own the New Indian HoldCo; and (ii) the New Indian HoldCo owns the Foreign HoldCo (directly) and the Indian WOS (indirectly) (explained better by the diagrams below). As compared to an inbound merger, where the Foreign HoldCo merges into the Indian WOS and ceases to exist, the Foreign HoldCo survives here – the shareholders can choose whether to liquidate it or let it remain as a subsidiary of the New Indian HoldCo.

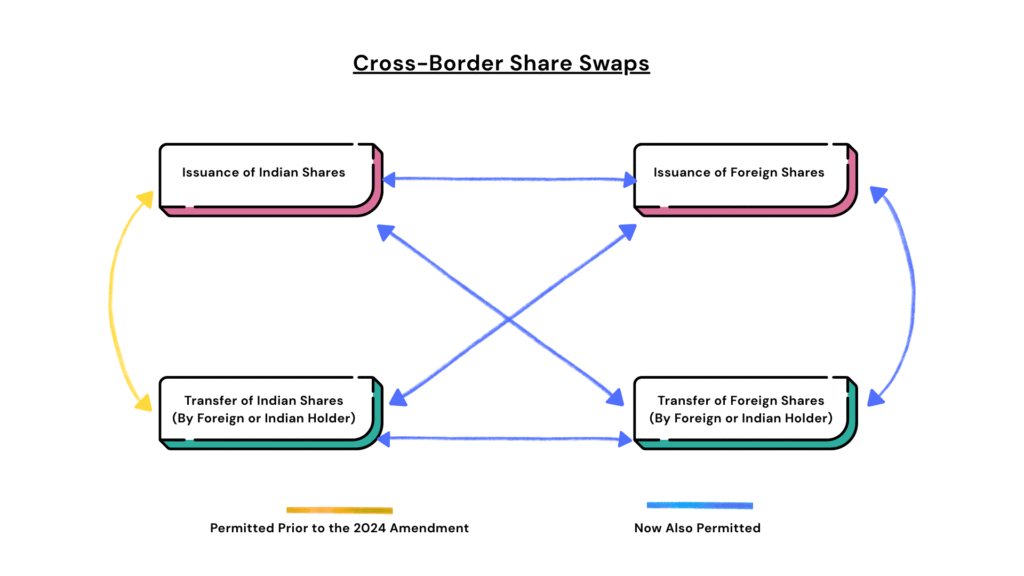

Its important to note that the above structure isn’t the only way to reverse flip via a share swap, but is perhaps the simplest. Being a contractual affair rather than a strictly statutory one like an inbound merger, share swaps allow startups and their lawyers to get creative in how and between whom shares are swapped. Room for such creativity was unlocked only recently, when the piece of Indian foreign investment law that governs share swaps was loosened up on August 16, 20247. Prior to the amendment, share swaps were only allowed in the context of an Indian company issuing its shares to a foreign resident and receiving the shares of another Indian company held by this foreign resident as payment. Cross border share swaps involving foreign company shares or paying an Indian shareholder in the form of shares (Indian or foreign) to purchase shares held by him in an Indian company (rather than being issued shares by the company) were entirely out of the picture. The lifting of these prohibitions in 2024 now allow endless permutations and combinations (as you may see in the diagram below).

Interestingly, the most famous company to reverse-flip using a share swap, i.e., PhonePe in 2022, managed to do so prior to the 2024 amendment. The structure they used to get around the restrictions on cross border share swaps at the time, however, isn’t public information (and hypothesising on how they must have done it is a task for another article).

A share swap is a vastly quicker process than an inbound merger, but it can rack up an eye-watering tax bill for shareholders. This is because the swapping of shares here is seen as a “transfer” under Indian tax law and attracts long term capital gains taxes on the appreciation in their value. PhonePe’s reverse flip cost shareholders a combined ~$1 billion in capital gains taxes. The blow didn’t end there. Indian tax law allows a loss-making company to use its accumulated losses over the years to reduce its tax liabilities later when it starts earning profits; PhonePe’s accumulated losses were reset to zero due to the reverse flip making them ineligible to claim tax benefits on them later. A tax bill like that may be digestible when your shareholders are Walmart, Tencent, and GIC but would strike terror in the hearts of other startups.

Wrapping Up

Inbound mergers and share swaps are tried and tested reverse-flipping methods, as seen above. This doesn’t mean they’re the only methods available. Based on their stage of growth and the laws of their foreign jurisdictions, startups may choose alternative options such as simply setting up a new structure based in India from scratch (if they’re at an early stage) or liquidating the Foreign HoldCo and transferring its assets (including shares of the Indian subsidiary) to its shareholders.

The Indian government has been considering the development of its own new route for reverse-flips as well: reverse-flipping to the IFSC GIFT City in Gujarat. The GIFT City was created in 2015 as a ‘global financial centre’ to be treated under law like a foreign jurisdiction located within India, with more relaxed business and investment regulations than the rest of the country. In 2023, a report prepared by a committee of industry old-timers (including Nikhil Kamath and Nishith Desai) pitched several ideas to encourage GIFT City as a destination for foreign-held startups to reverse-flip to. These included: (i) allowing the carrying forward of losses to claim tax benefits, which was denied to PhonePe; (ii) making incorporation easier; (iii) relaxing procedural compliances like mandatory filings, and (iv) the setting up of dedicated courts for commercial disputes. These suggestions are yet to be implemented.

Footnotes

- The inbound merger process was governed by: (i) Section 234 read with Sections 230-232 of the Companies Act, 2013, which outline the steps required for a foreign merger; (ii) the Companies (Compromises, Arrangement and Amalgamations) Rules, 2016, which zooms into the finer procedural details considered important enough to be law but just not enough to be included in the Companies Act; and (iii) the Foreign Exchange Management (Cross Border Merger) Regulations, 2018, which deals with the movement of money/ assets to and from India during a foreign merger. ↩︎

- Section 234(2) of the Companies Act, 2013 and Rule 25-A of the Companies (Compromises, Arrangement and Amalgamations) Rules, 2016. ↩︎

- Section 230(1)(a) of the Companies Act, 2013 and Rule 3 of the Amalgamation Rules. ↩︎

- (i) a notice of admission; (ii) all material information relating to the company; (iii) details of reduction in share capital of the company, if any; and (iv) an affidavit swearing that all information provided is true. Further documents would be required in case the merger involves a corporate debt restructuring. ↩︎

- via the insertion of Rule 25A(5) in the Companies (Compromises, Arrangements and Amalgamations) Rules, 2016. ↩︎

- Fast-track mergers are governed by Section 233 of the Companies Act, 2013, instead of the long and boring Sections 230-232. ↩︎

- via the insertion of Rule 9A in the Foreign Exchange Management (Non-Debt Instrument) Rules, 2019 ↩︎